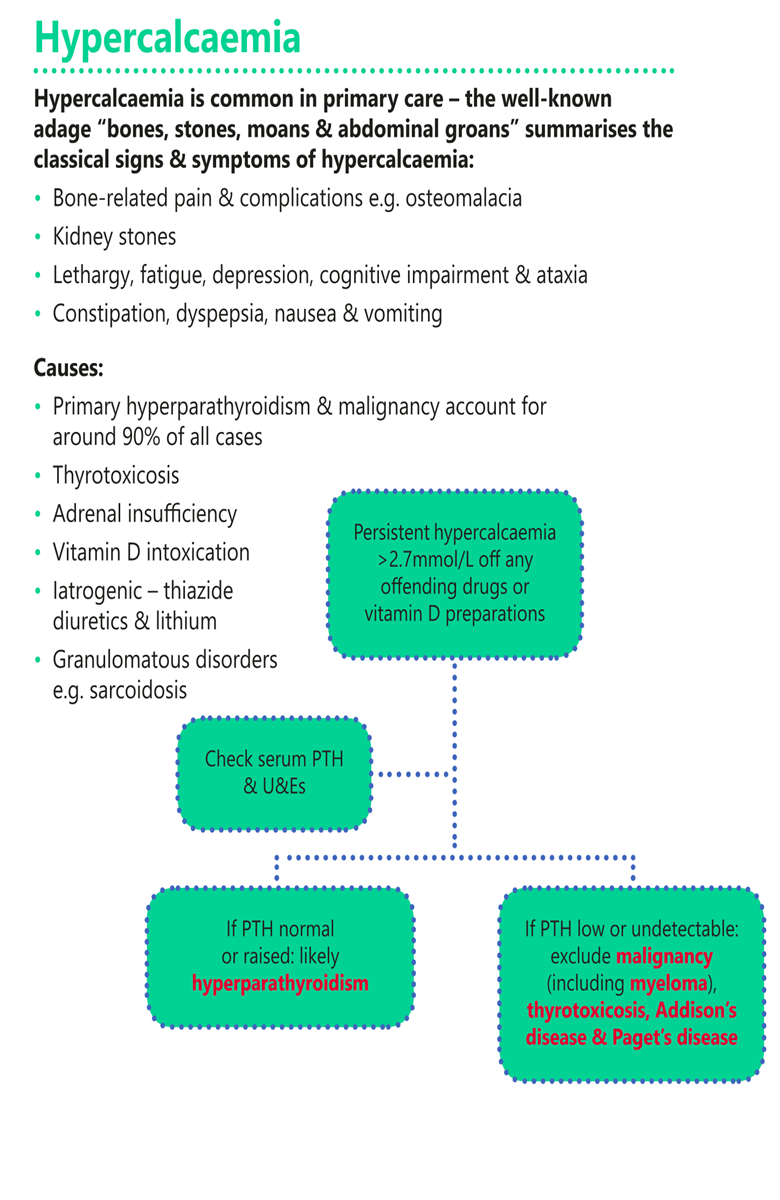

Hypercalcemia

An abnormally high level of plasma calcium i.e. greater than 2.6 mmol per liter

on two occasions

following correction for the serum albumin concentration (1).

Hypercalcemia can be classified according to the adjusted serum calcium concentration:

Mild – adjusted calcium concentration is 2.65 – 3.00 mmol/l

Moderate - adjusted calcium concentration is 3.00 – 3.40 mmol/l

Severe - adjusted calcium concentration is more than 3.40 mmol/l (1)

Note that reference ranges may vary between laboratories.

Reference:

(1) Smellie WS et al. Best practice in primary care pathology: review 11. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61(4):410-8

Aetiology of hypercalcaemia

The common causes of hypercalcaemia

which accounts for about 90% of cases

are due to primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy:

Primary hyperparathyroidism

commonest cause in the community (1),

accounts for 80% of cases

and is more important in the young

Malignancy

accounts for 20-30% of cases (1)

and is frequently accompanied by hypoalbuminaemia:

- suggested by rapidly increasing hypercalcaemia (1)

- metastases with osteolytic deposits e.g. breast

- osteoclast activating factors e.g. multiple myeloma

- ectopic parathyroid hormone like peptide e.g. hypernephroma, ovarian tumour, bronchial carcinoma

- 10-15% of hypercalcaemia caused by malignancy have associated hyperparathyroidism (2)

Rarer causes of hypercalcaemia include:

Increased extrarenal synthesis of calcitriol in chronic granulomatous disease:

- sarcoidosis

- pulmonary tuberculosis

- berylliosis

Addison's disease

Paget's disease with bed rest

Immobilisation - especially in adolescence when bone turnover is increased

Vitamin A and/or D toxicity

Drugs:

- thiazide diuretics

- lithium

Thyrotoxicosis:

- usually mild and accompanied by hypercalciuria

- due to increased bone turnover

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism

Milk alkali syndrome

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) (2,3)

Reference:

(1) Joshi D, Center JR, Eisman JA. Investigation of incidental hypercalcaemia. BMJ. 2009;339:b4613

(2) Barth, J.H., Butler, G.E. and Hammond, P.J. 2008. Hypercalcaemia. Biochemical Investigations in Laboratory Medicine. Leeds Teaching Hospitals.

(3) Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-66

Clinical features of hypercalcaemia

Many people are asymptomatic especially when they have mild hypercalcaemia` (1).

Features of hypercalcaemia may include (the mnemonic “Stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans,” can be used :

GIT problems “abdominal moans”:

- constipation

- nausea and vomiting

- peptic ulceration - due to increased gastrin secretion

- abdominal pain

- pancreatitis (1)

Psychological:

- depression is common

- dementia and psychoses occur infrequently

Renal “stones”:

- polyuria due to a decreased sensitivity to antidiuretic hormone

- compensatory polydipsia

- nephrolithiasis

- nephrocalcinosis (1)

Skeleton “bones”:

- bone pain

- arthritis

- osteoporosis (1)

Neuromuscular “psychic groans”:

- lethargy and fatigue

- weakness

- anorexia

- impaired concentration and memory (1)

Calcification:

- cornea

- conjunctival flare

- urolithiasis

- less commonly, chondrocalcinosis

Cardiovascular

- hypertension- shortened QT interval on electrocardiogram (1)

In severe hypercalcaemia (total calcium > 3.5 mmol per l):

- cardiac arrhythmias- renal tubular damage

- hypokalaemia, dehydration, sodium loss; renal vasoconstriction; acute renal failure

Reference:

(1) Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-66

Diagnosis

Hypercalceamia is diagnosed when there is an increase in corrected (or albumin adjusted) calcium concentration

above the upper limit of 2.65 mmol/l (1).

it is important to obtain adjusted (corrected) calcium levels

since low albumin levels will alter the total serum calcium levels (1)

Tests should be repeated

unless the patient has severe hypercalcaemia or symptoms which warrant immediate referral

Ionised calcium levels are not routinely done in primary care (1)

Patients with adjusted hypercalcaemia between 3 – 3.4 mmol/l

and symptomatic

or if adjusted levels are >.3.4 mmol/l

should be admitted to a hospital for urgent treatment (1).

If the hypercalcaemia is mild or moderate,

look for an underlying cause.

Possible biochemical indicators of malignancy include

- low plasma albumin,

- low chloride,

- raised phosphate,

- raised alkaline phosphatase,

- alkalosis

- and hypokalaemia.

Possible biochemical indicators of hyperparathyroidism are

- normal or low albumin,

- a normal or reduced phosphate,

- a raised PTH (or inappropriately in the normal range),

- and a normal urea.

PTH should be suppressed by high calcium concentration due to any other cause.

The exception is familial benign hypercalcaemia

where PTH may be normal or elevated

but when, unlike other causes,

the calcium excretion index (CEI) is low

despite high plasma calcium.

( CEI = [Ca] urine * [creat.] plasma / [creat.] urine)

Other biochemical indications:

Raised albumin + raised urea - implies dehydration

Raised albumin + normal urea - implies a cuffed sample

Normal or low albumin + normal or raised phosphate:

- Raised alkaline phosphatase - suggests bony metastases, sarcoidosis, or thyrotoxicosis

- Normal alkaline phosphatase - myeloma (raised plasma protein), vitamin D excess, milk-alkali syndrome, thyrotoxicosis, sarcoidosis

A ten day glucocorticoid suppression test may be diagnostically useful.

Note:

Prolonged application of a tourniquet should be avoided when obtaining a blood sample to test serum calcium concentration

Adjusted calcium levels is an approximate value and may be inaccurate in cases of extreme albumin concentrations

e.g. - patients with paraproteinemias (1)

Reference:

(1) Smellie WS et al. Best practice in primary care pathology: review 11. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61(4):410-8

Treatment of hypercalcaemia

Seek expert advice.

The underlying cause of the condition must be treated.

General measures aimed at lowering the serum calcium

1. Medications known to cause or worsen hypercalcaemia,

such as thiazide diuretics, should be discontinued

2. Avoid immobilisation

3. Generous oral salt and water intake should be maintained

- promotes calcium excretion

- avoids ECF volume depletion, which would exacerbate hypercalcaemia

Mild Hypercalaemia (less than 3 mmol/l)

most case caused by primary hyperparathyroidism

management of asymptomatic patients is controversial

to qualify for medical, and avoid surgical management

these patients should have, besides only a mild increase in serum calcium,

no previous episodes of life-threatening hypercalcaemia

and normal renal function

and normal bone density

Patients must be monitored closely with

- frequent questioning about symptoms,

- measurement of blood pressure, serum calcium, renal function,

- and possibly urinary calcium excretion,

- abdominal radiographs,

- and measurements of bone density

Specific indications for surgery in asymptomatic patients

with primary hyperparathyroidism are:

- raised serum calcium(>2·85 mmol/L or mg/dl)

- history of episode of life threatening hypercalcaemia

- reduced creatinine clearance

(<70% of that for age-matched healthy people)

- kidney stone(s)

- raised 24 h uniary calcium excretion(>100µmol or 400 mg)

- substantial reduction of bone mass

Immediate intervention directed at the mild hypercalcaemia itself is not usually necessary

In outpatients with mild primary hyperparathyroidism

All diuretics should be avoided

- Loop diuretics such as furosemide increase urine calcium excretion

but may also induce ECF volume depletion, increasing renal calcium resorption and worsening the hypercalcaemia

- thiazides are contraindicated

because they reduce urine calcium excretion and increase the serum calcium

Bisposphonates lower serum calcium but they are rarely required in mild hypercalcaemia

Moderate hypercalcaemia (calcium > 3mmol/l and < 3.375 mmol/l)

Treatment decisions depend on the severity of the symptoms,

which generally correlate with the

rate of rise

of the serum calciumIn patients with few or mild symptoms,

treatment of the underlying disorder

may decrease serum calcium

before symptoms become serious

When neurological symptoms are the sole manifestation of hypercalcaemia,

other reasons for the altered mental status changes must be excluded

before the symptoms are attributed to the raised serum calcium

If gastrointestinal or neurological symptoms are severe

it may be difficult simply to provide oral salt and water,

and intravenous normal saline may be required to restore intravascular volume,

leading to improved GFR

and enhanced renal calcium excretion

As the serum calcium falls, the renal tubular concentrating mechanism will improve, so stabilising intravascular volume

Gentle hydration with intravenous saline may be enough

but if congestive heart failure ensues

or if more rapid lowering of serum calcium is desired,

a loop diuretic will enhance calcium excretion

ECF volume depletion must be avoided because this will worsen hypercalcaemia

In a setting of renal insufficiency, higher doses of loop diuretics are needed

thiazide diuretics must be avoided

Intravenous saline plus a loop diuretic should decrease the serum calcium rapidly,

usually by 0·25-0·75 mmol/L in 1 or 2 days

if this reduction is insufficient bisphosphonate may be required.

Severe hypercalcaemia (calcium level above 3·375 mmol/L)

This requires immediate referral to the emergency department

treatment is via a combination of measures

- Enhancing volume repletion and renal calcium excretion,

- Reducing bone resorption,

- Targeting the underlying disease proces

If a raised PTH then should be referred for urgent parathyroidectomy

The usual reason for severe hypercalcaemia is malignancy

Initial treatment for the hypercalcaemia

is with intravenous normal saline and a loop diuretic

Monitoring of haemodynamic and electrolyte status is required

with intravenous hydration and a loop diuretic

Adequate rehydration with 0.9% saline e.g. 3-6 litres in 24 hr period as necessary

with potassium supplements, as indicated by serum monitoring

Serum calcium will fall rapidly

- however the effect lasts only as long as the infusion and diuresis continue

Correction of hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia using IV supplements

Monitor plasma sodium, potassium, magnesium, urea, CVP

Since osteoclast activity is usually enhanced -

Therefore treatments are directed at reducing bone resorption should be initiated using a bisphosphonate or other agent

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates have become the principal class of agent for the management of hypercalcaemia due to enhanced osteoclastic bone resorption

Bisphosphonates action to lower serum calcium

start to take effect after 48 hours

however the maximum effect may not be seen for 5 to 7 days.

Other agents Plicamycin (mithramycin)

inhibits osteoclastic RNA synthesis and decreases bone resorptionlower serum calcium more quickly than bisphosphonates therapy

Mithramycin inhibits bone resorption

- effective if due to hyperparathyroidism or malignancy

- but toxic to liver, kidneys and platelets

Calcitonin

Calcitonin inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption

and enhances renal calcium excretion

Calcitonin has an acute but very short-lived hypocalcaemic effect

Effect on calcium concentrations is modest and transient,

and calcitonin alone has no place in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia

In very severe cases - an excellent addition to the later-acting plicamycin or bisphosphonates

Gallium nitrate

binds to bone mineral and reduces hydroxyapatite crystal solubilitylike bisphosphonates, takes several days before a nadir in serum calcum is reached,

and this lasts about a week

side-effects are frequent and severe,

with nephrotoxicity, hypophosphataemia, and anaemia

Gallium should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency

or those receiving another nephrotoxic agent

Glucocorticoids

are effective in hypercalcaemia associated with haematological malignancy (lymphoma, multiple myeloma)

and in diseases related to 1,25(OH)2D3 excess, such as sarcoidosis and vitamin D toxicity

Haemodialysis

against low-calcium dialysate is more effective than peritoneal dialysis

for the dialysis- dependent hypercalcaemic patient

Reference:

(1) Prescribers' Journal 1999; 39 (4): 234-241.

(2) Bushinksy DA, Monk RD. Calcium. Lancet 1998; 352 (9124): 306-311.

(3) West Midlands Palliative Care Physicians (2012). Palliative care - guidelines for the use of drugs in symptom control.